by Lewis Johnson

At the opening press conference of the 16th Istanbul Bienal in the Osman Hamdi Room at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, curator Nicolas Bourriaud invited his audience to recall Werner Herzog’s film from 1982 Fitzcarraldo, in which a European trader living in South America in the nineteenth century, trying to build an opera house in the jungle, has to give up when the boat taking him to the heart of the jungle that thousands of locals are trying to drag over a mountain gets stuck. “God will finish the work”, says one of the characters, so Bourriaud reminded us, inviting us to imagine, despite the colonialist underpinnings of the plot of the film and the fact that the Europeans and the South Americans “never understand each other”, if not the infamous risks Herzog took which entailed serious injury to more than a few of those contracted to work with him, that, if the promise of this remark from within the fiction could not quite be put to the test, those artists selected to show work in The Seventh Continent might nevertheless be involved in supplying something of the lack of fulfilment or failure staged in Herzog’s notorious film. Courageously enough, however, as if in echo of something of the reality of the making of the film as well as of its fiction, the curator of the Istanbul Bienal seemed to have accepted that its successes might only be partial. The exhibition was not simply to be taken as “ecological”, even while it is the first biennial, he said, “to move for environmental reasons”, following the discovery of asbestos at the Istanbul shipyard buildings where the majority of the 56 artists and artist groups invited to participate were due to show. Translated at short notice from there to the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, opened ahead of its due date early next year, the curator’s contention that what is known as the seventh continent, that mass of largely plastic debris, once discarded into the oceans, now forming a mass five times larger than Turkey floating in the Pacific, is also everywhere, in our air, food and water, was uncannily apt: for those familiar with Istanbul, where intensive demolition and rebuilding of recent years, coupled with the suspension or bypassing of legal processes of approval or inspection—as at the site of the new museum itself—has rendered unidentified encounters with risky substances the new norm.

It is also uncanny to recall how the 13th Istanbul Bienal was required to move, from sites outdoors to Antrepo 5, the warehouse building now demolished, the site of which between the new museum and the waterfront is now a building site where a series of structures comprising the development once rejected by the nation’s High Court as not in the interests of the people are currently being constructed. The 13th from 2013, the year of the Gezi protests, haunts the 16th, with the art changing locations late in the day, the new museum now something of surreal landscape, calm and easy, with the 38 exhibitions numbered and viewable in sequence, yet sometimes functioning as a platform from which to view, sometimes hear and smell, the massive constructions and huge excavations taking place outside. At the press conference, the curator invited us to imagine the artists tangling with ancient as well as current forces, with fictions, their own and that of others, including those in play in such disciplines of knowledge as archaeology, and acting as translators between humans and the non-human. He went so far as to claim that there was a sort of “molecular anthropology” being undertaken by some, observing interactions even between molecules and non-humans. Beautiful as this figure of the artist as translator seemed, where translation is both spatial and concerned with language, I wondered whether “molecular anthropology” was not something of categorical slip, echoing something of all-too-human desires to recover—or recover from failures of—control that the notion of the Anthropocene, the theoretico-historical notion of humanity’s alteration of the planet as eco- or biosphere, can also be understood to memorialise and re-motivate. What about other modes of knowledge, the so-called hard sciences such as biology or physics, applied sciences such as medicine or engineering, or, in other contexts, human sciences such as sociology or political science? As I went round the three sites of this ambitious exhibition, I found myself asking what sorts of knowledges and knowing were being brought into question. Provoked to ask what sorts of artistic strategies were being deployed to do this, I began to wonder how important the displacement of any one form of knowing, including that associated with claims to high art, as with Fitzcarraldo in the Amazonian jungle, might come to seem.

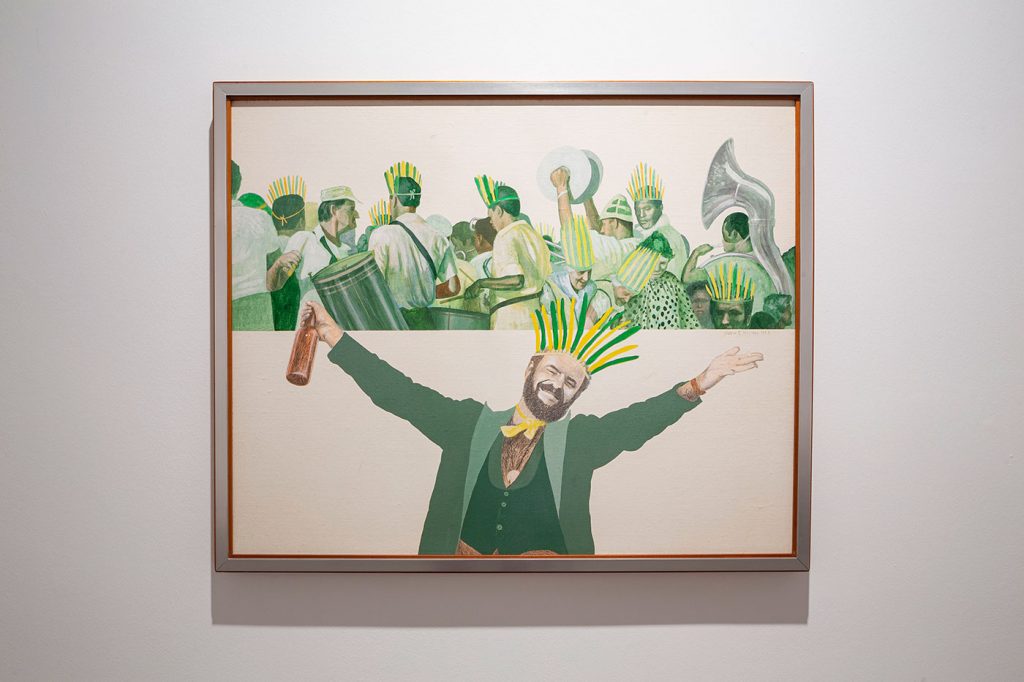

Glauco Rodrigues, Earth Vision Legend of the Coati Puru what is it?, 1977, installation view at Pera Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

Perhaps the best place to start with this challenging biennial is not the new museum, but the selection of older work by artists in Pera Museum that is offered as prefiguring more recent concerns. A painting from 1977 by Brazilian artist Glauco Rodrigues associated with Critical Tropicalismo seemed to satirize political appropriation of indigenous festival culture, though the wall-text specifies “white power”. Perhaps the difference is now moot, given Bolsanaro’s mobilization of indigenousness as key part of a promised Brazilian resurgence. Along with this are selected pieces by Spanish artist Anzo, whose dark paintings suggest dystopic senses of computational machines and architectural and city spaces, reminding me of some of Yüksel Arslan’s concerns, and work by Alberta Porta known first as Evru, and then Zush, deploying a range of styles of painting and print-making suggestive of imaginary solar systems, but also humanoid figures, perhaps of other planets. The uncertainty bites back, however, with suggestions of dystopias here predominating. The extensive display of objects from U.S. artist Norman Daly’s Llhuros, the series of artefacts begun in the 1960s and contemporary with the other artists here, works to instantiate, through patient and careful citation of modernist primitivist styles, both this imaginary civilization, its practical, decorative, artistic and ritual activities, and a way of working that calls into question pretensions of archaeology to comprehensive knowledge of a past culture. How to understand what also comes along with this as a question of affirmation of artistic making and process is a more difficult issue, but Daly’s ambitious project haunts Pera, mixing with the mix of its collections, as well as with the rest of the Bienal.

Simon Starling, Infestation Piece (Mask for Istanbul), 2019, installation view at Pera Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by David Levene.

There is no one answer, I would say, to this question of the value of artistic making, even if one sort of artistic working will inevitably call up others to provoke this sort of question. As if to insist on the importance of negotiating with this, notable recent work at Pera Museum shares in something of a disparity between artistic vocabularies. Part of what has been persuasive about much of Simon Starling’s work is the ambitious consistency of plans and execution of projects, whether this has involved the remaking from photographs and transportation of furniture across the globe, or the casting of sculptural forms in steel deriving from electron-scanned matrices of data. Chance and formal variation have taken on a more prominent role in his Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2006-8), a copy of a piece by British sculptor Henry Moore that Starling submerged in Lake Ontario, colonized by zebra mussels, an invasive species deriving from the Black Sea, which was later, in the Canadian museum, also invaded by a colony of moths. Alongside two opulent photos of the conservators trying to separate moths from sculptural copy while leaving the mussel shells behind, is a new infestation piece, a mask with extravagant earpieces oddly echoing the butterfly-form of more of the zebra mussel shells. Was Infestation Piece (Mask for Istanbul) submerged in the Black Sea? Detailing a history of U.K. Arts Council’s promotion of Moore that involved Anthony Blunt, art historian and double agent for the U.S.S.R., Starling’s use of disparate sources also recalls Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers’ series of assemblages with mussel shells, which were also satirical of the claims of national culture. Alongside Starling’s work is Melvin Moti’s Cosmism, a video abruptly shifting from footage showing what is—the guide informs us—a dramatic reconstruction of Mary Stuart’s execution, found footage from the streets of lower Manhattan on 9/11 and shots of solar flares, perhaps suggesting questions about cosmic-type causes, as the guide mentions, but also inviting questions of genre. Infection of uncertainty about the source of footage of people wandering the streets almost lost in the silence of clouds of dust also augments the sense of realities out there in the solar system and the destructive power thereof, perhaps hinting in the direction of what Bernard Stiegler invites us to think in terms of the “Neganthropocene”, the question of how to participate in a negentropic prolongation of life as sustained on this planet in this solar system.

The brilliant disparities of Charles Avery’s work twist and turn across registers of the realistic: large-scale drawn pieces representing aspects of life on his imagined island, with the struggles in and around the port city of Onomatopoeia—named teasingly after a solution to a problem of naming—to the fore, surrounding a spreading market-stall-type display of lustrously realistic sea creatures in glass. In The Exform, Bourriaud developed a series of arguments concerning the importance for art since Courbet of a Realism that desires to follow what Youssef Ishaghpour termed “the materiality of nature”. Bourriaud accepts Linda Nochlin’s account of Courbet’s L’Atelier as representing the “Fourierist ideal of the Association of Capital, of Labor, and of Talent”, but stresses Courbet’s aim to awaken spectatorial “action, engagement, and the capacity for transformation” through the materiality of artistic means. Thus, despite the implication that the artist’s use of Fourier’s ambitious terms to represent those he knew mattered too, Bourriaud’s history of ways in which art has disturbed supposed senses of reality by means of “the Real” constructs a lineage from Courbet and Manet to Beuys that insists on a confrontation with the materiality of the means of art as the means to a passage to the other side of ideology. Perhaps The Seventh Continent might be thought of as an extended experiment with the argument developed in The Exform that Bataille’s heterology, opposing “the science of the wholly other” to homogeneous representations of the world as such, uncovers the affinity between art and waste. But is this on the side of potlatch or the residues of the petrochemical industries that have clustered together in the Pacific? Bourriaud picks out how contemporary art seems poised between “sociocultural utility and its dysfunctional quality”, but it is not clear that the dysfunctional it introduces and works with is locatable exactly on the side of its material means.

Pakui Hardware, Extrakorporal, 2019, installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo Sahir Uğur Eren.

The positioning of Rebecca Belmore’s beautifully sinister metal curtain-like sculptural piece Body of Water near the entrance of the new museum may signal a curatorial desire for this sense of the material to win out, but, in containing a canoe, it also works towards a relation to commemoration, if also a sense of a removal from view, of those First Nations teenagers found dead following a spate of racist murders in Lake Thunder, Ontario. The range of experimental work with material, though also with materialities—how materials can be thought—in the new museum is impressive. Recalling Haacke’s Condensation Cube, while rediscovering a historical aspect to the experimentation with the duration of looking, Dora Buder’s cuboid chambers puff up pigmented matter recalling the cobalt blues, shadowy pinks, acid yellows and oranges of J.M.W. Turner’s paintings, recently re-read as witness of atmospheric traces of Anthropocenic activity, though this is not simply without precedent given long-standing accounts of anti-industrialism and anti-mechanism through his work. Nearby are further re-explorations of art historical lexicons, but in view of senses of space for bodies in Mariechen Danz’s ambitious reworkings of the boundaries of the sculptural and the architectural. We return to questions of materialities more obviously in play in work by Latvian artist duo Pakui Hardware, Neringa Cerniauskaite and Ugnius Gelguda, that, both installation and sculpture, continues their interest in synthetic biology and regenerative medicine, melding matter of familiar and unfamiliar sources, glass, leather, but also artificial furs and gelatinous silicons, into hanging and protuberant forms suggestive of mixed animal, human and unknown other existents or existents-to-be hung up for inspection. The inclusion of Johannes Büttner’s striking upside-down sculptural figures molded of earth but with skeletal plastic or other machine parts suggests rather different interests in the sculptural. Echoing Georg Baselitz but in sculpture, Büttner’s fighting figures are removed from clear possibilities of action, and, like Baselitz, somewhat of emotion. Some also produce sound, with their skeletal parts too, now and again, threatening greater animation, suggesting that the violence they represent is not quite subdued.

There are other important opportunities to consider the roles of the sonic in contemporary art elsewhere in the show. Of course, this is often a significant feature of the video work in the show, such as Phillip Zach’s Double Mouthed, a double projection on opposite walls of a single room of footage from the ancient Yarımburgaz cave near Istanbul opposite similar from the Bronson Cave outside Los Angeles. Similar not only in being from inside a cave, however, for the caves are also as different as might be, with Bronson being man-made for the film industry. The insistence of the cinematic or televisual dramatic is often carried by sound, as we find out with more documentary footage of both sites interspersed with clips from dramas filmed in both caves, including cult Turkish ‘sword and sandal’ Tarkan films of the late 1960s and 70s. Jennifer Deger of the Feral Atlas Collective suggested, on stage with Phillip Zach at the public lecture programme at Pera Museum on the Bienal’s first Saturday, that Zach’s piece destabilises senses of history, and, with his insistence on unknown outcomes, this involves not only senses of ancient and Deep or geological time, but also attempts to represent it. Elsewhere in the museum, Mika Rottenberg’s use of sound adds to the peculiar rhythms of the events and their editing in Spaghetti Blockchain. Recalling something of the abrupt transitions of animation, Rottenberg combines the unlikely with the unfamiliar, mixing events staged in colourful interiors with more obviously public spaces of assembly lines and sites of corporate agribusiness. Sound is often punctual here, providing a sense of the real in relation to the hallucinogenic. Recalling the curator’s interest in these terms in The Exform, it might be noted that accounts of “the Real” deriving from the work of Jacques Lacan differ in their stress on whether its experience involves something more on the side of the drive and interiority or in a relation to exteriority. Admitting both, however, would tend to undermine any would-be magical effect of uses of the term. Rottenberg’s compelling weave of spaces also brings out how sound can be motivated as interruption of dystopic, visually-communicated realities.

Radcliffe Bailey, Nommo, 2019, installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo Sahir Uğur Eren.

This is also notably the case in the memorable sculptural-installation piece by U.S. artist Radcliffe Bailey, a large, high, curved, open-ended section of white-stained wooden planks containing seven small busts of what look like the same Black man. Recalling the deep hulls of the slave ships, the form also acts as a soundbox for a piece by the experimental, jazz-inspired, cosmicly-inclined Sun Ra Arkestra, but also of the sounds of waves on a beach accompanying the sounds of boat-building and boat-builders in Senegal. At the public programme at Pera Museum, French historian of civilizations Laurent de Sutter pointed out how the Middle Passage of ‘the’ Slave Trade, the transportation of Black Africans to the Americas by Europeans, lines up between the establishment of settled agricultural communities and Industrial Revolution as debated originary causes of the Anthropocene. Alerted by Stiegler, Bailey’s piece can also remind us that this is something of a moot point. Oscillating uncontrollably between debates about human power and apocalyptic powerlessness, there is a danger of being caught in failed mourning, which attention to horrific realities, if partly imagined ones, of the Middle Passage and to kinds of cultural survival may help to address. The comings and goings of sound are also set in train in the installation work of Brazilian artist Anna Bella Geiger along with disparities of scale between small, delicate models of something like an ancient Middle Eastern settlement laid out on the floor and a video, alternately informative and animated, of the meanings of the site accompanied by extracts from Philip Glass’ opera Akhnaten about the adopting of monotheism in Ancient Egypt. Taiwanese artist En Man Chang’s model and video installation about a migrant community in Taipei that helped to build the city that later became the object of relocation by the government communicates not only the inhumanity of state policies, but also the oneiric characteristics of the city, with the delicate models of streets, new high-rises but also the machinery of building catching the changing colourful light of the video projection, ironically remaking the city’s promise.

Anna Bella Geiger, Circa, 2006/2019, installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Lewis Johnson.

The chance to consider changing artistic strategies in respect of changing genres of contemporary work—almost more than contemporary, with so much of the work on show being commissioned for the event—also takes in versions of performance-related work. Ylva Snöfrid’s large-scale installation of painted work Fantasia is the ongoing outcome of her work in situ in the museum, deploying elevations of wall- and furniture-like panels painted with, among other motifs, repeating facial features, evoking the utopic as well as the dys- and heterotopic in family life and elsewhere. Jared Madere has wall-drawn Dubuffet-esque figures in lipstick, draping translucent banners printed with kinds of popular cultural images, group portraits with children in particular, although a Mini Cooper car hanging framed with white LED lights takes centre-stage. At least, this seemed so until young children from the local Italian school were invited to be judged in a smiling contest, the one who could smile the longest getting their rice with honey first, cooked more or less enticingly in the room. Adults were there to look after the children, perhaps partly in view of the anxieties the masked man—Madere’s collaborator—who judged and handed out the rice seemed to evoke in some. This excessive intensification of the styles of popular, if not populist, culture put its toleration to the test. Whether the work also established a relation to a mode of generous exchange—as the Bienal guide claims—is more questionable. Recent delegated performance art, from Santiago Sierra to the somewhat more charming Tino Sehgal, has tended to demand things participants in art have seemed not to give, or be unwilling so to do. As such, such recent work may be marked out from earlier delegated performance work that tended to convoke what were typically presented as willing participants in transformational experiences. This dividing line has become blurred, however, for instance in the work of Monster Chetwynd, whose commission of a climbing-frame sculpture in the Sanatçılar Parkı in Maçka is at once for children, “mildly provocative” as she put it, in deriving its central orifice, the main ground level exit from the parkland structure, from the sculpted gorgon heads in Yerebatan underground cistern, and also the site of a performance orchestrated by the artist of a group of teenage girl dancers. I did not see this performance, but at the public programme the artist talked briefly about her dance training and how even clichéd movements, for instance of a group sweeping down towards a central object, could be moving. Her other work echoes some of these emphases: four, slightly outsize, more and less clichéd spooky figures at the entrance to a disused wooden house on Büyükada, the third main site of the Bienal, which, as painted, if cheap models can also be read as generically complex, a sort of frieze-as-installation of what has seeped out from the haunting, if not haunted house.

Jared Madere, Pavillion du Voyageurs, 2019, installation view at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren.

Before turning to the other work on the island in conclusion, l will return to the new museum building to note the contributions of several Turkish among other artists there and to an issue of participation that will lead me to the terms of that conclusion. Work by Turkish artists struck me initially as modest. This included Deniz Aktaş’ drawn pieces in ink, including his new, subtly allegorical pieces, The Ruins of Hope, Elmas Deniz’s model-making, found objects and drawings that explore the alteration of flows of water in Istanbul and ancient Gryneion near Bergama, and Müge Yılmaz’s floor piece with wall-hung, stencil-like structures switching in and out of prehistoric art and later modernist land art vocabularies. Despite its size, the large-scale installation on the top floor by Güneş Terkol and Güçlü Öztekin also seems modest, certainly in its use of fabric, pigment and cardboard, if not with its seating areas providing an extensive social space for visitors. Modesty of means, then, does not simply correlate with what is just mild or even polite, as Monster Chetwynd may have already clued us in to think. The selection of work by Agnieszka Kurant, from what looks like a pleasantly colourful, vaguely organicist abstract painting, but which turns out to be an electronic liquid crystal display translating algorithmic accounts of alterations in sentiment on particular websites, to the sculptural melding of samples of ossified car paint known as Fordite from around the globe, to the similarly spherical miniature bezoar stones, from animal digestive systems, arranged in miniature minimalist style in a display case, shares in obscurities in their apparent obviousness. At the public programme, Kurant’s account of her work stressed the undermining of human autonomy, referring to her impressive pigmented sculptural work as if co-authored with termites. Yet in the museum, her piece delicately welding together metal multiples by Beuys, Carsten Holler and Carol Bove has a humour that calls into question ambitious metallurgic sculpture, if also a lineage of masculine positionality in relation to this sort of artistic authorship. What seems modest can also, as art, be poised to draw on newly vital ambitions, convoking new senses of the social.

Deniz Aktaş, The Ruins of Hope I, 2019, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren.

Agnieska Kurant, Mutations and Liquid Assets I, 2014, installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Sahir Ugur Eren.

This biennial flows best in this sort of direction, it seems to me, as one might expect from a show curated by the author of Relational Aesthetics. The memorable series of luminously white pieces by Simon Fujiwara—if also by his large group of Turkish model-making helpers—coupling found, imperfect or broken casts of characters from popular animations with professional-standard architectural models of hospitals, stations and other public constructions invites a look that is distanced and absorbed, as if lost in a dystopic processing of populations. Eva Kot’átková’s dramatic installation, Machine for Restoring Empathy, brings the question of art’s relation to shared social exchanges more to the fore. With the attendants on hand also to share in accounts of what has been, and what might yet be made from the assortment of fabrics and other materials on show as well as of the narrative workshop, texts from which are also on display, the dwelling-like object made of outsized human clothing constructions sits oddly with the smaller, more eloquent fish and bird related pieces. These disparities and their contents suggest imaginative exploration of different zones and modes of inhabitation, which may help imagination to measure up to the current radical disaster underway of the failures of co-existence with other species on this planet, as it concerns more obviously the many and various pieces that comprise the Feral Atlas Collective display. Mapping the unintended consequences of Anthropocenic environmental activities, from the lethal ingesting by albatrosses of plastic bottle tops and the like they cannot distinguish from food filmed by Chris Jordan, an exercise in the mourning mentioned above, to underwater noise pollution of ships in the Artic Ocean blocking mating by sea creatures, the display interestingly pushes at the limits of what has gone feral. Led by anthropologists, the work of this group of academics, authors and artists insists—despite its “humanist” tag—on what may seem an old postmodern problematic: the Lyotardian side-effect as what returns through the modern. Rejections of this sort of questioning in new discourses of the modern or the up-to-date, termed “inhumanist” by Laurent de Sutter in the public programme, presumably stigmatising Lyotard, cannot minimise the desperate need for acknowledgment of the complexity of the limits of the powers of the human, the heteronomy of the effects of its agency in interaction with what such historians tend now to call infrastructures, and for explorations of materials and materialities, and sociabilities and socialities, as part of more responsive ways of living.

Hale Tenger, Suret, Zuhur, Tezahür / Appearance, 2019, installation view at Taş Mektep, Büyükada, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by David Levene.

On Büyükada, which can sometimes itself seem to be something of an experiment in historical forms of social life, with its horse-drawn vehicles, grand houses, and sites of shared religious veneration, the 16th Istanbul Bienal continues to impress. Hale Tenger has made the garden of what was once the house of the Ecumenical Patriarch, later a Republican school, now a stone shell, into the site of an interventionist sonic, literary and sculptural piece. Subtly installed, speakers convey the sound of her reading her poem in which linguistic identification with the objects of the practice of tree girdling—a classical technique of cutting into the trunk to accelerate growth, but which would typically lead to an early death—invites, in this space, with its series of haunting obsidian mirrors and ground-level water trays, both a re-imagining of historical gender oppression and of this and other sites of exploitation beyond renewal. The apples that grow here are not now large or without imperfections, but they can be eaten. Glenn Ligon has installed Sedat Pakay’s film about James Baldwin’s time in Istanbul, between 1961 and 1970, now subtitled in Turkish, and extemporised in video on some of the notable sites of the city to selected music of Black America. The hanging light piece using mahyas, those lights hung from minarets during Ramadan, spelling out ‘America’ upside-down plays something of a risky game with cultural codes, groups and the values of authorship. Sometimes, as with the selection of Piotr Uklański in Pera Museum, Tala Madani, Ambera Wellmann and Haegue Yang in the new museum, or perhaps Andrea Zettel on the island, it is not clear how the work is to be construed in relation to the informing issues of this biennial exhibition. If you have made it this far with this review, you may already sense that I would like to think that these selections were driven by compelling solicitations of different ways of thinking what is social, its exclusions and inclusions, what is typically left unthought and what may be rethought, among other matters. Sometimes, however, it rather seems as if this has been considered without quite being thought through, much as the ambition of the curatorial proposal would encourage us to do.

Armin Linke, Prospecting Ocean, 2018, installation view at Sarı Ev, Büyükada, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019. Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren.

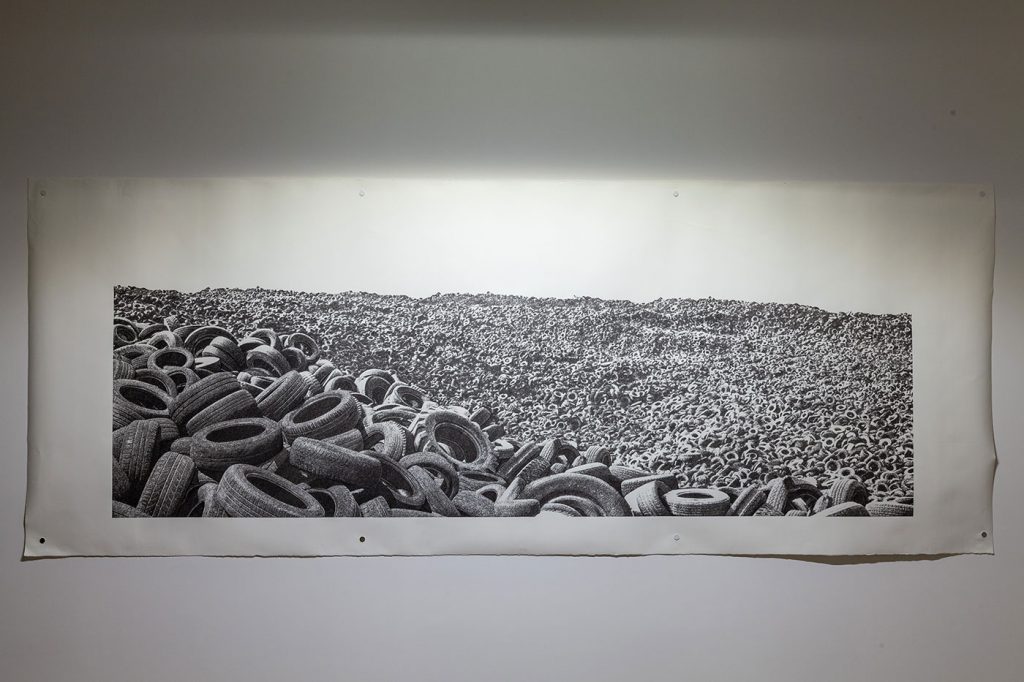

I have left to last what I take to be one of the most persuasive pairings that comprise this Bienal, of work by Armin Linke and Ursula Mayer in the Sarı Ev of the Anatolian Club on the island. On the raised ground floor is Linke’s extensive and sobering Prospecting Ocean, an installation of videos, documents, maps and illustrations, detailing historical and current interests at work in the mapping and exploration of the seas. With videos about activist groups in Papua New Guinea working to get their voices heard, international negotiations concerning marine rights and tensions over what is acknowledged as being in the common interest, Linke’s work is also animated by a concern to question the terms of the visual representation of marine life as traceable, for instance in the works of his fellow countryman Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, early Italian Enlightenment oceanographer, who worked on marine life in the Bosphorus. Walking around the installation, one’s look might stray out of the window only to find it scanning the masses and the zones of the sea, that putative object under consideration within the space. Letting the sea be would thus be part of how to share in what its wealth might mean. This is clearly enough a complex social and—given the dramas mapped out by Linke’s ambitious work—political matter, put on view to be seen and remarked, even while the work does more than simply represent it as such. Indeed, in the context of this Bienal, the vitrines of early illustrations of fish, typical specimens though they may have been taken to be, echo the work of Feral Atlas Collective and many others here in communicating questions of co-existence between human and other groups, drawing us into questions of which cultures and practices may best serve the vital diversity of forms of life on the planet.

Upstairs, something rather different awaits, but this video animation by Ursula Mayer is something that, according to the delay its slowly rhythmic movements inscribe, invites speculation on the meanings and senses of this female figure in reticulated dress that variously rises and falls, pauses, and beckons to her viewers. Avatar-like, this figure of trans model Valentijn de Hingh may be taken or recalled as suspended, as if overwhelmed by challenges past or yet to come. Inheritor of something angelic, but both darker and lighter, this uncanny figure may also help to recall and re-imagine the multiplicity of roles suggested in game and other forms of contemporary visual cultures, though not infrequently suppressed in the wider cultures they participate in, inviting us to join in with new modes of co-existence to come.

God has not, it seems, come along to finish the work in the jungle. The work of the 16th Istanbul Bienal, artistic and curatorial, dystopic and desperate though things may seem, solicits us to re-think and re-imagine how to do without such a sense of endings, while even better understanding others.