A conversation on the collapse of hierarchies established by our ways of thinking about the world, and how to take lessons from the anthropocene.

by Anna Zizlsperger

Nicolas Bourriaud, curator of the 16th Istanbul Biennial titled The Seventh Continent, 2019, Photo by Muhsin Akgün

I remember that Elmgreen and Dragset, the curators of the last Istanbul Biennial in 2017, were asked to boycott the biennial due to the political situation in the country. Have you been asked the same question?

I agree with them, and don’t think boycotts work. It does work for brands, that’s what boycotts were invented for. But I don’t see the point in boycotting a whole country. You just leave this country isolated, and that is excactly what autoritarian regimes want. Are we boycotting America because of Trump, or China ? There are more efficient ways to fight against them. But when I accepted to work here, it was to say whatever I wanted to. If there had been censorship or pressures, I would have left, but that has not been the case. If you integrate or internalise censorship, then you have already lost.

Do you feel that you were in any way restricted by the political situation in Turkey? Did you even think about it?

I was approached to curate this biennial the same way I would have curated it in China or anywhere else. First, there are multiple allusions to the situation in Turkey in the biennial. Secondly, the very fact that I propose contents here that I could have shown somewhere else is another answer to the situation.

How have you found the experience of working in Turkey?

I have actually been here many times, every two years at least, to visit the biennials, or to give lectures in the 2000s, at the invitation of Ali Akay. So I did actuallly have a sense of the situation here. I didn’t have a totally naive gaze on Istanbul: it was informed by previous stays.

I am sure you have all kinds of great offers for projects. Why did you decide to curate the Istanbul Biennial?

For me the Istanbul Biennial is the number two in the world, after Venice. Historically speaking, it was the first biennial not to have national representation, at the opposite of Venice and São Paulo. So it has a history of its own. And it is the biennial that generates authorship. In Venice you are always lost in thousands of parasitic events. Here in Istanbul, it is really the occasion to develop a point of view and that’s what I liked when I started seeing Istanbul Biennials. Since the beginning of the 2000s I have seen them all — except the last two, unfortunately, for diverse reasons. Also, I must confess I have always dreamt of working in such a city.

Was there any particular biennial that stood out to you?

I remember almost all of them, from Yuko Hasegawa’s “ecofugal“, or Hou Hanru and Charles Esche spreading out all over the city. I tried to do the opposite of them actually, as I wanted a very concentrated exhibition : the times are not propitious to the discovery of Istanbul wonders, or even its cultural life. This year I wanted to bring something to Istanbul, not the opposite.

On that note – the main venue of the biennial got cancelled in the build-up to the event. Could you give us some details on that?

Yes, that was both unfortunate and strong. The Istanbul Shipyards were supposed to be the exhibition’s main venue, and were completely ready on August 1st. Some of the artworks were already inside. This would have been finished by mid-August. So cancelling our main venue was a very difficult but courageous decision to take, and it was about standing against toxic gentrification. Because we could have stayed. Most of the people would have stayed, but if we are actually dealing with environmental issues like this biennial does, it is not possible to take any risk with public health. It was our duty also to inform the public about these kinds of toxic gentrification processes in Istanbul, and the IKSV was very brave about it.

The new venue is the Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture – Antrepo 5. How did you deal with this big change and how does it affect the exhibition?

My exhibitional layout was based on the shape of the old venue, so it had to be forgotten. I used the same elements, including all of the artists’ projects, but could not connect them in the way I planned originally. So the exhibition had to be remixed… In such a small amount of time, and being given the spaces offered by the new buidling, it was necessary to rethink all the sequences, almost all the associations. I assembled them in a different way, generating a different feeling, adapting the ground-floor continuous space we had at the Istanbul Shipyards to a four-storey museum. I had worked with the first space for a whole year. It’s frustrating, but that’s life: you cope with it.

Mariechen Danz, Body Bricks, 2019

2455 clay bricks individually imprinted with images using models of human organs and the body itself (replica of original brick from the historical shipyards, Golden Horn), Installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019, Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

Eva Koťátková, Machine for Restorating Empathy, installation view at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019, Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

Could you talk about the curatorial design of the biennial and how it changed in the transition from the original venue to the new venue?

At the shipyards, it was actually a big warehouse space, divided in two by a series of arches. The first room was a room of bifurcation: you could choose either the right path or the left path. If you went to the left path, there was a sequence of artworks depicting a very harsh reality. It was about installing a kind of landscape – the landscape of the capitalocene – in a quite realistic way. And if you went for the right path, there was a much more poetic answer to the situation. On this path, you found artists inventing rituals, artists referring to ancient civilizations, etc. This double helix path went on till the middle of the space, with another moment of bifurcation. It is like an unrealised project, that we kept track of in the catalogue.

What have you prepared for the biennial in terms of publishing?

There is a guidebook and a catalogue: very classical. The catalogue, titled « Field report », starts with a long essay, « Theses on art at the era of global warming », goes on with a collective text written by all the artists of the biennial, ‘reply to all’. It’s a very convivial space for elaborating ideas. Then, there is a visual section, creating new pairings between all the artists’ works, that I added after the change of venue : it was, in a way, a third and last « remix » of the exhibition.

How is curating a biennial different from other types of exhibitions and can you talk about your experience curating this particular biennial?

With this kind of exhibition, it is the confrontation between the artworks that is very dynamic: it’s not one work specifically, but rather the dialogues between them. It is the choral effect produced by the entire exhibition. The sound of the capitalocene…

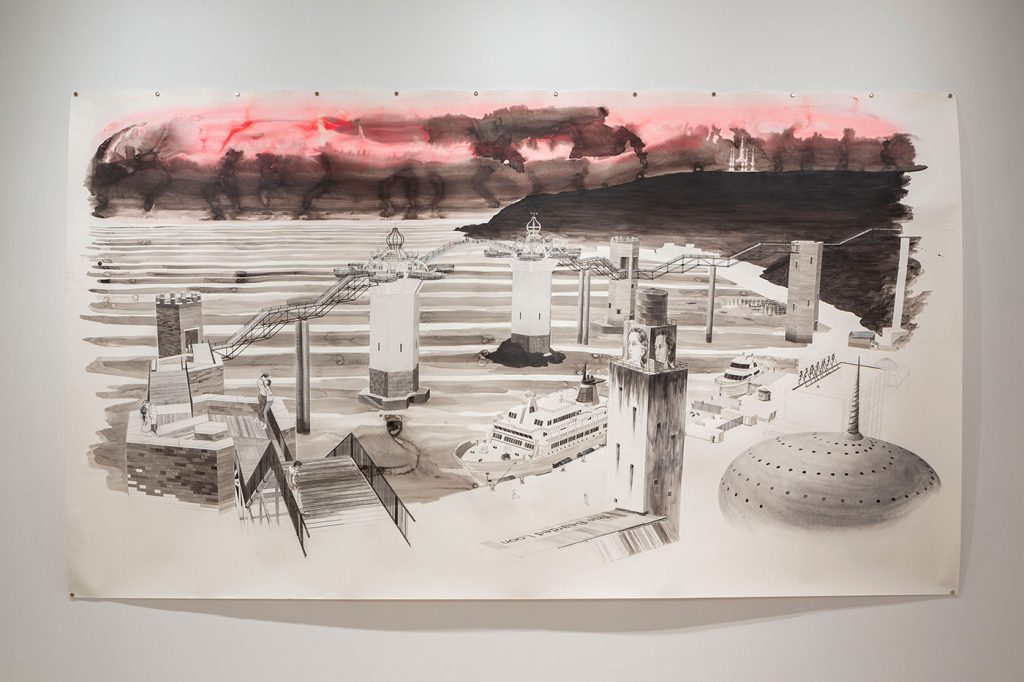

Charles Avery, The Islanders, installation view at Pera Museum Istanbul, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019, Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

Charles Avery, The Islanders, Untitled, installation view at Pera Museum Istanbul, Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

Is there a certain opposition that you created that you would like to talk about?

I would say that the main opposition is between the statements about the situation on one hand – the idea of dealing with waste, desolation, desertification etc. – and on the other hand, the capacity that artists have to invent new civilizational elements. The exhibition at Pera Museum will be mainly devoted to artists who practice a sort of imaginary archaeology. The archaeology of ficticious worlds, like Norman Daly inventing the civilization of Llhuros, or Charles Avery inventing an island-universe, which is the source of all his writings, sculptures and drawings. It is important to understand that this is not a form of escapism. Imagination is not a way to escape the situation, but it is a way to describe it from another point of view, as if there were a plan B, or an alternative. It is important to do a detour via fiction to understand reality. So the main dialectical movement in this exhibition would be between raw reality and fiction, between two anthropologies.

Sanam Khatibi, I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye, 2019, installation view at Pera Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019, Photo by David Levene

Can you talk about the other venues?

Büyükada is a kind of parenthesis, at the end of the process: a gathering of works that need more time – like Armin Linke or Glenn Ligon. Also some outdoor projects, like Monster Chetwynd or Andrea Zittel, who was originally proposing one of the few outdoor projects at the shipyards. The idea was not to disperse in the city and spread the exhibition out but to keep this concentrated structure, and Buyukada is a wrapping-up of all its themes in a outdoor situation.

Andrea Zittel, Personal Plots, 2019, sculpture made of concrete blocks demarcating human-sized cell-like spaces, installation view at Büyükada, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019

Photo by Onur Doğman

Could you give us some more words on the curatorial concept – why you feel this is the time to make this biennial in istanbul?

The question this biennial answers to would be along the lines of the following: what is the impact of the anthropocene on our ways of representing and thinking the world? More specficially, what are its effects on the way that artists produce forms? These might be the main questions. It represents a moment of shift, of transition. Because the anthropocene could be summed up by one very simple image: It is the collapse of the hierarchies established by our ways of thinking the world.

It is the collapse of the division of nature and culture, the collapse of hierarchies between different realms and spheres that we consider as severed and separated, like humans, animals and plants etc. We are obliged to have a holistic representation of the world, and this changes everything. We have to be more aware of global consequences of apparently small decisions. The butterfly effect is now part of our everyday lives. And this is where we have to place our attention. This has a strong impact on the artists, and they have antennae for these kinds of things. In studios and in exhibitions today, you can really foresee this way of thinking that will spread out tomorrow. So this is what the exhibition is about: about taking lessons from the capitalocene, seeing how the artist becomes a translator between different worlds, translating the voice of the minerals, of matter, of animals… Organizing a kind of pan-dialogical world. This produces new systems of representation, and that’s the interesting part of it. And I haven’t yet taken all lessons of it myself yet. Actually when I go to see the final exhibition, I am sure there will be other ideas. I mean this kind of gathering around very focused problematics will certainly bring something else that I hadn’t thought of yet.

Feral Atlas Collective, installation view at at Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 2019, Photo by Sahir Uğur Eren

A large percentage of the works in the biennial are commissioned. Is this something you feel is important to do in a biennial exhibition?

Yes, I think a biennial is also an opportunity to offer artists a possibility of taking a step in their work. But sometimes it is also interesting to show already exisiting work. I am not this kind of curator who thinks that once an artwork has been exhibited, I should pass to something else. On the contrary, I actually think it is really important to re-show, to re-exhibit in different contexts, to highlight the different layers of meanings that are in the artworks.

How did you select the artists?

It is a never-ending process. I have notebooks full of artists’ names and according to the exhibition, there is a nucleus of 5-10 that I think are obvious. Then every artist leads to another one, and so on. It is a mosaic way of thinking.

Could you tell us about that nucleus?

There were maybe a dozen artists I wanted to work with, whose work I discovered more recently, and also a few ones that I wanted to go further with after the Taipei Biennial I curated in 2014, The Great Acceleration, which was the first exhibition I did about the anthropocene. The Seventh Continent is in some way a part of a trilogy, starting with The Great Acceleration and then Crash Test, the “Anthropocene Trilogy“.

What do you think about the contemporary art scene in Turkey?

I discovered very interesting artists, even if all of them did not fit with this specific exhibition. Even though I visited many exhibitions and archives, and gathered portfolios. So I just regret that I don’t have another year to explore more.

The title of the biennial, The Seventh Continent, has a very clear connection to ecology, which is an increasingly public subject at the moment. Many people might ask what that has to do with contemporary art and why you put the biennial in this context?

Well, it goes largely beyond contemporary art, but that is why it is an interesting issue to explore. The Seventh Continent is the name for this huge mass of plastic waste foating in the oceans, and I take it as the image that determines the whole exhibition. First, it is a negative space. As a continent, it is the exact inverse of the new world “discovered“ by Christopher Columbus, because this is the start of the Western colonization process, and I see the seventh continent as its end. It is its absolute negative counterpart : nobody wants to settle on there. It is the shadow of our hyperproduction, the shadow of our economic system: it is the exact image nobody wants to see. So the idea of the exhibition was to position the artists as the anthropologists of this new continent, like as if it were a new territory to discover: a kind of anti-colonization of a place nobody wants to be in. In the expanded anthropology I am referring to in this exhibition, I insist upon the work of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, or Eduardo Kohn, who wrote How Forests Think. It is an anthropology that is not only about humans, but about humans within a non-human, dialogical context. That is the kind of anthropology that I see in effect in contemporary art today.The British anthropologist Tim Ingold defined anthropology as “philosophy with the people in”. It is this kind of anthropological practice that is at the core of the biennial. Anthropology as producing knowledge from and with people, from and with the new beings we encounter, humans or not… Even the distinction between who and what, he, she and it should be reconsidered in light of the anthropocene. It is a process of interaction, curiosity and acknowledging otherness, acknowledging the other. Considering the other as the only real source of knowlege.

As a philosopher, what is your take on the political world’s current swing away from unity and towards exclusion and othering?

One could say it is the last moment for this kind of petrified generation of politicians. They are afraid: like horses feeling that there is a storm coming, they build walls to protect themselves. So if we are optimistic, one could say it is their last rally.

The core of this kind of reactionary politics is actually the negation of the other, like Bolsonaro exterminating the Amazonian people, or Trump allowing building a wall with Mexico. For both of them, at the core of their actions is the idea of disemboweling and exploiting the soil, it is kind of rapist mentality.

I agree. I think what we have done and continue to do to the planet is shocking. Equally, that there is so little public awareness of the issue. You feel official media outlets should take more responsability, but they just focus on other issues instead.

You know, that’s pollution too: it is part of the pollution system. Something that is going to be very important in the years to come is working on the different levels of pollution we are confronted with, not only physical pollution, but also mental and social pollution. Pollution is everywhere.

The way social media is deteriorating our attention span comes to mind.

It is the replacement of desire by pulsions and impulses. Impulses are instant movements, desire has to be articulated. Desire is a long-term construction. Impulses are instant reactions. We are shifting from a civilization of desires to a civilization of impulses, which is a bad news.

Do you feel French?

Not really, frankly, I don’t. You know when people say “my culture“ – everyone’s culture is a mosaic of very different things, unless you are actually completely wrapped up in your own national garments. But I have been exposed to so many different kinds of influences and ways of seeing the world, that I feel like a kaleidoscope of elements coming from very diverse places. I made a theory of it in my book Radicant. It is the idea of growing your roots, not depending on the original one. Ivy and strawbery plants actually grow their roots while advancing. I am a radicant.