by Selin Tamtekin

Neriman Polat can be regarded as a cult figure in Turkey’s contemporary art scene. She has been creating prolifically since the early 1990s, and her work continues to undertake some of the most pressing and problematic issues facing Turkey.

Neriman Polat, Private Security, 2013, photograph 63 x 123cm, courtesy of the artist.

In the 1990s, Turkey witnessed a breakthrough in art as pioneering artists of this era abandoned modernist aspirations to engage with social themes such as identity, gender politics and popular culture. Polat still carries the inquisitive temperament and discourse of this period close to her heart as she bravely delves into modernization, urban transformation, gender inequality, violence (particularly towards women and children) and racial discrimination. A sceptic of the art market, and still embodying the collective spirit of the 90’s, she has refused to commit herself to any gallery, while she continues to devote her creative energy to initiating and collaborating on art projects that carry a strong social incentive.

Neriman Polat, Breaking the Seal, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

A Recurring Theme: Gender Inequality and its Ramifications

Whether playfully suggestive or unapologetically direct, in Polat’s practice there is always an underlying display of reckoning, or a rebellion against the mechanisms of patriarchal power and coercion.

Private Security (2013) a reclining female figure – an image charged with art-historical references – portrays the notion of the woman – if with an undertone of wry humour – as someone who must always remain alert to safeguard herself. In Turkey, as in many other countries across the globe, women are still subjugated and under threat of male violence and abuse. The recent #MeToo movement has publicised how sexual harassment towards women is a worldwide ongoing epidemic that has no borders. A report by Sezgin Tanrıkulu, a Turkish human rights lawyer and member of Parliament (as reported on the Turkish news website, Diken, on 7 March 2019) claims that between 2002 and 2018 a staggering 15,034 Turkish women’s lives were violated. The report also claims that during these 16 years femicides increased sevenfold. The alarming surge in femicides in recent years suggests that gender inequality and its social ramifications are serious problems that need to be addressed from multiple channels.

Breaking Those Seals

Breaking the Seal, is a retrospective spread out over two floors of Depo Istanbul’s spacious public venue. It displays a carefully selected range of iconic pieces and multiple-part installations (some, reconfigured in new ways) from the start of Polat’s artistic career in the 1990s, up until this year. Befitting with the artist’s collective spirit, the exhibition has two curators, Derya Yücel and Wenda Koyuncu. In a phone interview, Koyuncu explained to me that their curatorial strategy was to focus on the main themes the artist has dedicated herself to over the years, and to create a dialogue between the works, while also drawing emphasis to the media the artist opts to work with – namely installation, photography, video art and textiles – as a way of representing her diverse visual oeuvre.

Backpack, 2013, installation view Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

When I speak to the artist a week after her exhibition’s preview, I first ask her what the title, Breaking the Seal, refers to.

Polat responds: It’s to do with tampering with all those identities that have been stamped on us like a seal. Our passports, our ID cards all contain these seals. Being a woman, a Turkish citizen, being Middle Eastern, I think such definitions limit our lives and our realm of freedom. It is important to break those seals. As an artist who voices radical, oppositional ideas, I am someone who’s naturally inclined to meddling with seals, so to speak. Also, the title refers to my artistic practice, which is not limited to a studio but is action based and very dependent on observing the life outside.

A Path to Liberation Through Women’s Solidarity

In the exhibition, The Backpack (2013), an oversized black monochrome backpack, filled to the brim, has been placed on the gallery floor to connote, according to the artist, notions of unsettlement, of belonging nowhere. Elsewhere, The Threshold (2013), a six-frame video piece, projected onto a wall, depicts six different women carrying the same bulky black backpack on their backs as they pass through separate thresholds in various locations, leaving their homes and lives behind, loudly banging their front doors behind them. Both works were made in 2013, the year the Gezi Park protests broke out – a pivotal turning point in the country’s recent history – and evoke the sight of numerous protestors flocking to the park with their large backpacks, stuffed with portable tents and personal items. Although the artist agrees the influence of Gezi Park is evident in both works, the oversized backpack fundamentally symbolizes the circumstantial differences between men and women. According to Polat, in Turkey, women typically carry heavier baggage than men; therefore, it’s a much more cumbersome affair for them to leave, to go out to the streets, since when they do, it is never on equal terms. At the very end of The Threshold, we see the six women united, repeating the same act together – a finale that symbolizes a path to liberation through women’s solidarity.

Neriman Polat, Threshold, 2013, video projection, 04.44 minutes, courtesy of the artist.

Flower Wound: A Dedication to Murdered Women

On the first floor of the exhibition, nearly covering an entire wide wall from one end to the other, is Flower Wound (2019), an imposing installation with long drapes of cascading flannel fabric. The artist has painstakingly manipulated the flower pattern of the soft fabric at certain intervals with a sharp razor blade knife – an arduous procedure which has taken her roughly three months.

Neriman Polat, Flower Wound, 2019, manipulated flannel fabric, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

When I ask Polat how she came up with the method, she responds: I have worked with flannel fabric prior to this. Things actually came to me when I was playing with the fabric and randomly happened to make incisions on it with a razor blade knife. There’s always a period of discovery followed by a period of deliberation. Once I decided to make the piece, I tried various different fabrics to see what gave the best effect of what I was after. I wished the flowers to appear like a wound, a bleeding or a bullet hole. I imagined each altered flower as a woman who has been snatched out of life. I did this work as a dedication to all the women who have been murdered in Turkey, but the viewer doesn’t have to see it in that way, since this information is not openly given to them. Its anti-monumental work, fluid and adaptable to different interiors.

The Personal is Political

As much as Polat is an ardent feminist, she is also a human rights defender, an activist through her art who urges us not to forget some of the haunting events that have shaped Turkey’s recent past.

Do we forget too easily? I ask her.

Yes, our society has a problem with memory, with facing up to things. But also, in the last ten years we have been constantly bombarded with such intense violence and calamities that in order to cope we try to erase these incidents from our memory. As an artist I try very hard not to forget. If ‘Elvan’ was killed I have to keep remembering this, if ‘Suruç’ happened I must not forget. And also, possibly not forgive.[1]

I then ask Polat what triggers her, on a more personal level, to render such challenging topics. To which she responds: I also feel like ‘the other.’ I am a woman who earns a living and who has her own struggle in society. I might be just an observer when it comes to big social traumas, but you still experience these on some level and one must resist being made to lose one’s empathy towards them. As an artist I have the incentive not to stay silent. Having said that, I don’t believe in using art as an ideological tool. Art is an individualistic practice, but it is also possible to heighten awareness towards important social issues through one’s work. As the 70’s feminist motto goes ‘the personal is political’ and effects everyone.

Neriman Polat, They Came, 2016, 168 x 98cm, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Through the Eyes of a Child

They Came (2016), a diptych made out of two infants’ blankets, hangs unpretentiously unframed, over a wall painted austerely in grey. The artist has altered the innocently chirpy tone of the blankets by painting over their original prints – Walt Disney’s animation character Bambi, pretty butterflies and flowers in pastel hues – with black and grey acrylic paint. Above the first blanket she has inscribed in illuminating white paint the newspaper heading ‘Öğretmenim Şehri Terk Etti (My Teacher left the City), from an article published on 13 December 2015 in Cumhuriyet newspaper. According to this article, teachers assigned to schools located in the South-Eastern Kurdish region received an SMS text from the Ministry of Education advising them to leave their posts and vacate these towns and cities before a state of curfew was declared and armed conflicts took place. As if wishing to put on record, the artist has listed one by one the names of these towns and cities in the bottom of the fabric.

Polat says, I was very effected by what happened and wished to render it through the eyes of a child.

On the second blanket the word Geldiler (They Came) is repeated alongside the already existing pattern of butterflies that have transformed into ominous dark silhouettes. Together their repetitive pattern echoes a child’s unending nightmare of hell.

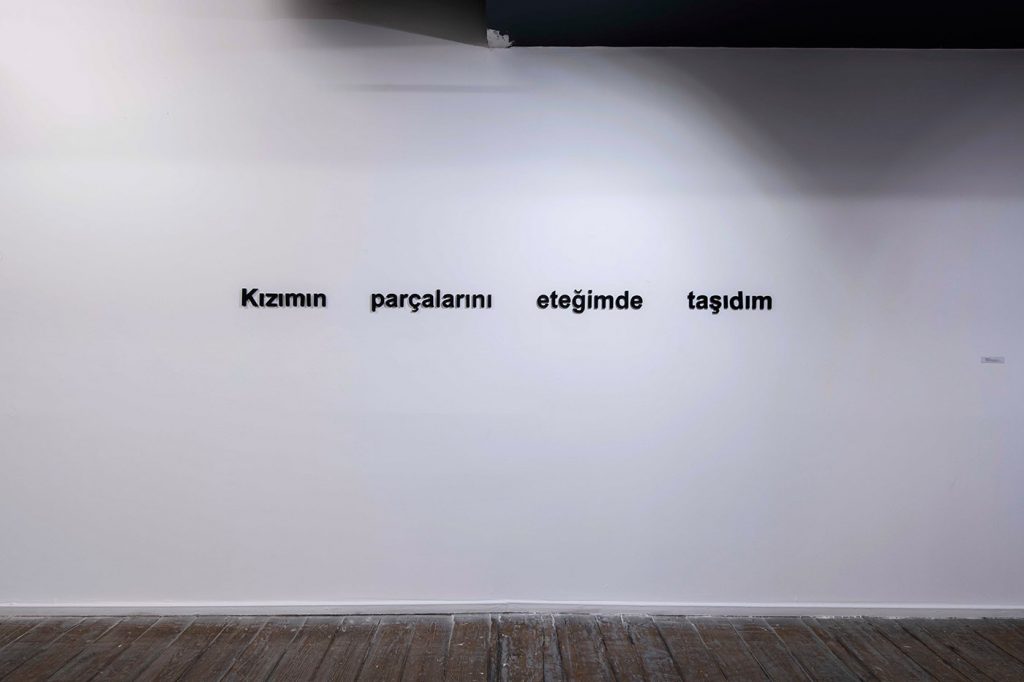

Neriman Polat, Ceylan (2011) ‘I carried my Daughter’s Pieces in My Skirt’, text installation, 280 x 9 x 1cm, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Kızımın Parçalarını Eteğimde Taşıdım, (I Carried My Daughter’s Pieces in My Skirt), the heading of an article published on 2 October 2009 in Taraf newspaper, is mounted in a reductive manner, using the same font as the article, directly onto the plain white gallery wall. The chilling words were uttered by Ceylan Önkol’s mother, who had to carry her twelve year-old daughter’s remains after she had been killed by a mortar shell fired by officials as she was playing outside in Şenlik, a village also situated in South-Eastern Turkey.

Polat says: This is one of the most severe sentences this country has seen. I transferred the title exactly as it was printed in the article onto the wall in three dimensions, because I wish to illustrate how when you put some distance between something as tragic as this, in a way you can sense the gravity of what’s happened way more than you would if you were to portray a dismembered body.

Neriman Polat, Breaking the Seal, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Depo Istanbul: A Symbol of Cultural Resistance

Depo Istanbul is a former tobacco warehouse in the district of Tophane that has been converted to a three-storey project space. Since its inauguration in 2009, with exhibitions, panel discussions, screenings and workshops, the venue has developed into a cultural hub where socially and politically engaged projects are realised.

Over the years, Depo Istanbul has become a symbol of cultural resistance, a notion that has been further enhanced since its chairman, philanthropist Osman Kavala, remains in jail following his arrest in October 2017 with allegations of financing the Gezi Park protests. Last month, the European Court of Human Rights announced that Osman Kavala had been detained arbitrarily and in violation with the European Convention on Human Rights, and called for his immediate release.

With its incentive to open its doors to alternative voices, this non-profit space is one of a kind and a life-support for the development of innovative art practices in Turkey.

The two most recent Istanbul Biennials have received criticism from the foreign press for steering well clear of themes of human rights and freedom of expression, or for excluding local artists who overtly delve into contemporary Turkish politics, which these days, might not be so easy to find. As Koyuncu points out, in the aftermath of the Gezi Park protests there has been a notable decline in artists engaging in political issues, and a visible increase in artworks dedicated to nature and the environment.

Koyuncu adds: The avant-garde attitude of the 90’s seems to be abandoned these days. Particularly when you consider things from that angle, you can appreciate how valuable this exhibition is for our times.

Neriman Polat, The Glove, 2013, photograph 50 x 42.5cm, installation view, Depo Istanbul. Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

An Odd Mixture of Melancholy and Hope

Plastic Glove (2013), a small photograph resting unassumingly against a column, arouses an odd mixture of melancholy and hope. It ties in with some of the artist’s earliest pieces in the exhibition, which explore existential queries of the subconscious, yet this photograph also brings to mind the street art of colourful live performances and sardonically rebellious graffiti that had emerged during Gezi Park.

Polat says: It’s a glove that says, despite everything, we wish for peace.

Neriman Polat :Breaking the Seal: A Selection

of Works from 1996 – 2019, continues at Depo

Istanbul until 12 January 2020.

[1] Here Polat refers to 15 year-old Elvan Berkin who, after being hit by a tear gas cannister fired by a police officer during the Gezi Park Protests in Istanbul, died on March 11 2014, following a 269-day coma; and to the horrific attack carried out in the South-Eastern town of Suruç by an ISIS suicide bomber in 20 July 2015 which killed 33 and wounded 104 youth activists.