A review by Lotte Laub

Les Rencontres d’Arles: A Pillar of Smoke. A Look at Turkey’s Contemporary Scene, curated by Ilgın Deniz Akseloğlu and Yann Perreau

“Photography is often the best-placed medium for registering all the shocks that remind us that the world is changing, sometimes right before our eyes.” These are the words of Sam Stourdzé, director of the photo festival Les Rencontres d’Arles, whose 49th edition is taking place this summer from July 2nd to September 23rd in the south of France. In its official programme, Les Rencontres d’Arles has thirty-six exhibitions at thirty venues, including historical places, such as medieval churches and museums, in addition to galleries, former warehouses or abandoned houses. There are newcomers among the photographers shown, but also collections of historical photographs. The immediacy to which Stourdzé refers in the above quotation applies particularly to one of the exhibitions in the ‘Le Monde tel qu’il va / The World As It Is’ section at Arles, namely ‘Une Colonne de Fumée / A Pillar of Smoke’, curated by Ilgın Deniz Akseloğlu and Yann Perreau, which is on show at the Maison des Peintres, a two-storey abandoned house on Boulevard Emile Combes.

Positioned at the entrance to the ‘A Pillar of Smoke’ exhibition is a small cube with a miniature figure embedded in it. The cube is light blue and transparent, and it looks like a cut-out of a swimming pool. The cube is mounted on a pedestal and the figure is visible from above and from all sides. It’s a pleasant sight on first glance: we’re in Arles, it’s hot outside and inside, actually too hot for the artworks as well as for the visitors; also, Arles is not located on the coast, so you could easily be dreaming of diving into a swimming pool to cool down. However, it is unusual for the figure in this pool to be wearing a dress, seemingly made out of light gauze, like dancewear. Her toes touch the floor, her head is bent backwards, her face, neutral, is just above water, and her arms are floating in the water. Looking at the piece again, it isn’t clear whether the figure is actually enjoying the refreshing, life-giving water, or whether she is more focused on preventing herself from drowning, i.e. she could be in a life-threatening situation. The title of this piece by Sinem Dişli is ‘On the Verge (Self-Portrait)’, which also suggests some kind of struggle.

Sinem Dişli, Left: On the verge, 2018, [self-portrait] Sculpture and mixed media, 27 x 27 x 26 cm / Right: Sand in a whirlwind, 2015, Archival Pigment Print, 130 × 180 cm

Arles has a long tradition with photography. It was the first city in France to open a photography department in a municipal museum, the Musée Réattu, in 1965. The photo festival has existed since 1970 and is thus the oldest event of its kind in Europe and one of the most important gatherings on the photography scene. Arles isn’t just well known for photography, as it is also linked with another important name in art history: Vincent van Gogh. Although no van Gogh painting was on display in Arles until 2014 (when the Fondation van Gogh opened), the artist spent over fourteen months here and the city was the inspiration behind many world-famous works, including the Night Café (1888), which still exists today. It was also during van Gogh’s time in Arles that he was on the verge of insanity (the name of a 2016 exhibition in Amsterdam), as evidenced by his painting Self-Portrait With a Bandaged Ear. But what does the ear of van Gogh have to do with the exhibition A Pillar of Smoke?

To stand on the verge, to question one’s own existence as an artist, is an old topos that becomes virulent, especially in times of political unrest and war. L’art pour l’art, or taking a stance, even by merely documenting what happens “right before our eyes”, are different approaches that artists can take, and it’s the latter that is represented in ‘A Pillar of Smoke’. In its selection of both journalistic and artistic works, the exhibition keeps track of what is happening in the world and thereby deconstructs the official discourse. In some parts of the exhibition, we are being explicitly informed about current events, for example the room dedicated to the Gezi protests in 2013. It features a series of initiatives, including Turkey’s new media journalism project 140journos, which, according to Time magazine, has changed the face of journalism in the country. But there are also a number of works here where documentation is less explicit, where the expression of the artist’s voice also includes the negation of it, i.e. becoming and being silent, moving beyond speech. Remaining on the verge of explicitness may be related to questions of censorship and self-censorship, but perhaps also to the immediacy of artistic processing when facing an open wound, i.e. being confronted with catastrophic developments

Opposite Sinem Dişli’s water cube is her photograph ‘Sand in a Whirlwind’, and we can note a strong parallel between the two works: the longitudinal axis of the body, the tips of the toes touching the ground, the face above the surface of the water. In the photograph it is a pillar of sand that forms the central axis, extending from a barren landscape at the lower edge of the picture up into the sky, which we have to imagine beyond the upper edge of the picture, out of sight, as if a vengeful power were at work. This formal connection between a cube and photography, which arises via the longitudinal axis, points to the common theme of both works. Dişli is referring to a very specific phenomenon associated with her hometown Urfa in southeast Turkey. Although this Anatolian city became rich thanks to the dams on the Euphrates River, villages and Mesopotamian ruins were also flooded and erased from the map as a result. Local residents were displaced and there were water shortages and droughts beyond the Turkish border, in Syria and Iraq, causing sandstorms that boomeranged back into Turkey. Dişli’s work denounces this cross-border ecological disaster. We understand the message: Mesopotamia, home to the earliest human settlements and the Paradise rivers of ancient times, the Euphrates and Tigris, has been turned to an inhospitable area through ruthless exploitation.

Cengiz Tekin, Low Pressure, 2017, HD Video, 5 minutes 19 seconds, Courtesy Pilot Gallery

How do we deal with radical historical changes, when the familiar and generally accepted concept network no longer conforms to reality? When, deprived of an escape route, the degree of tension becomes unbearable? Cengiz Tekin’s video ‘Low Pressure’ (2017) appears to show that a poetic style may be a way of handling irrationality too. ‘Low Pressure’ can be described as an “audio-visual poem of silence”, a phrase used by Işın Önol, the co-curator with Ekmel Ertan of the exhibition ‘Black Noise’ (2017) in Istanbul where ‘Low Pressure’ was first shown. The video was shot in Tekin’s hometown of Diyarbakir. It shows the construction site for a future building. Reinforcing bars protrude from a concrete floor and mark out vertical meshes of quadrangular spaces. Young men, actors, run back and forth like caged tigers, roughly in the same rhythm as the soundtrack, which was composed by Cevdet Erek who represented the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017. As Önol has aptly stated: “This rhythm brings the tension where energy accumulates without finding a chance to release.”

There’s no text. Are the many restless-looking young men perhaps in the process of finding a way out, a solution to a problematic situation? Are they facing the dilemma of staying in a hopeless situation or leaving with the risk of failure? The structure of the video is in three parts with the first phase followed by a static middle section. You’re looking at the same scene but this time it’s deserted. Shortly before the end you see some actors again, but this time there’s only two of them, measuring their limited space in the same way as at the beginning. The gradual desertion of the rebar environment leaves room for questions and assumptions: where are the young men now? Did they want to build a house, figuratively speaking a future, and then they did not have the means to do, or were they prevented from doing so? Or did they flee? Or are they prisoners? Or is the video a depiction of the absurdity of human existence, the empty middle section a reflection of the futility of all efforts? The young men have gone away, been expelled or abducted, or died. The work they began is left abandoned.

Ali Kazma shows two videos, ‘Prison’ (2013) and ‘School’ (2013), from his series Resistance. Two screens are mounted on opposite walls with a bench is positioned in the middle, preventing viewers from seeing both videos at the same time. The theme of both videos is the subjection of the body to regimentation, either through discipline or supervision. ‘Prison’ was recorded in the Sakarya detention centre in Turkey; ‘School’ at the Galatasaray School in Istanbul. Filmed at night, both locations have something scary about them, and it is especially their desertedness that intensifies their threatening impression. It is as if the viewer were the first to enter the danger zone.

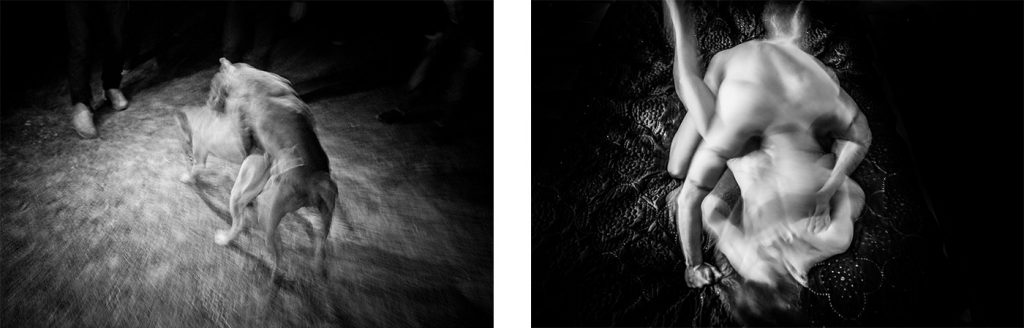

Çağdaş Erdoğan’s series ‘Control’ (2016) is its own small parcours within ‘A Pillar of Smoke’, beginning with night shots from a surveillance camera. The other photos have also been taken at night, but in this case the light setting – high-contrast black and white shots – consciously stages the event. In Erdoğan’s photographs, we see illegal dog fighting alongside prostitution, and both seem to blur into each other. Erdogan illuminates everything that is officially banned, repressed or ignored. The suggestion is that the more the restrictions in a country increase, the more active the underground scene becomes. Erdoğan exposes the subversive power of a particular underworld, breaking taboos in order to shed light on circumstances hidden from public discourse. At the same time, the work is also about the omnipotence of money and the hypocrisy of a regime that dissolves all human relationships. He shows his resistance and opposition openly and considers this to be a necessary stance sooner or later all around the world.

Çağdaş Erdoğan, Control Series, 2015-2016

In the last part of the exhibition, there are two rooms showing photographs by Nilbar Güreş. These photos work very well in the rooms of the deserted Maison des Peintres with its peeling walls and patterned tile floors. In her series ‘TrabZONE’, based on Trabzon, the artist’s Anatolian homeland on the Black Sea, Güreş shows surrealistic photographs reminding her of the summer of her childhood. A photograph from the series ‘Ana-Kiz/Mother-Daughter’ (2010) depicts two generations, mother and daughter, standing on the edge of a road and looking out into the distance. It could be a normal scene, but Güreş injects confusing dreamlike elements into her photographs. We see both figures from behind, standing side by side with a certain distance between them, but the same patterned headscarf is stretched over both heads. The veil symbolises social conventions, connecting the two bodies, but at the same time the two signposts point in opposite directions, symbolising the parting of their ways. While many works in ‘A Pillar of Smoke’ deal with freedom of expression, this photograph explores the tension between tradition and an individual’s liberation from restrictive social conventions.

Nilbar Güres, Ana-Kız (Mother-Daughter) from the series TrabZONE, 2010

The final image in the exhibition shows two boys from behind, one of them pointing with his outstretched arm into the distance, at a pillar of smoke across the border with Syria. We are reminded of Sinem Dişli’s pillar-of-sand photo in the first room. ‘A Pillar of Smoke’ uses both motifs to create a formal framework, both the pillar of sand and the column of smoke resulting from bomb attacks, signs of approaching man-made disasters.

‘A Pillar of Smoke’ was curated for Les Rencontres d’Arles for a French and international audience. ‘Regards sur la scène contemporaine turque’ / ‘A Look at Turkey’s Contemporary Scene’, the subtitle of the exhibition, thus sets a geographical focus, not necessarily on the contemporary photography scene in Turkey, but rather on the artistic processing of disturbing political developments. In view of the massive changes in Turkish politics, there is a question about whether controversial topics, such as the undermining of freedom of expression, should be tackled, or whether a different picture should be presented. The curators were therefore faced with a dual responsibility, namely to take a critical look at contemporary history but without falling into the trap of potential stereotyping. As Yann Perreau points out: “One should always avoid generalisation and reductionism when it comes to artists’ work and ideas.” The two curators have succeeded in presenting a great diversity of works.

Photo books of the individual series, for example by Çağdaş Erdoğan or Korhan Karayosal, the latter’s photo essay dealing with social gatherings in Turkey in an increasingly divided society, were featured on the bookstand at the Istanbul Photobook Festival during the satellite event Cosmos-Arles Books, which was held during the opening week of the Rencontres d’Arles and was one of this year’s main meeting points at the Arles festival. Books by both established and upcoming photo artists from Turkey were also on show at the satellite event.

The exhibition ‘A Pillar of Smoke’ features works by 140journos, Halil Altındere, Volkan Aslan, Kürşad Bayhan, Cihan Demiral, Sinem Dişli, Mathias Depardon, Çağdaş Erdoğan, Nilbar Güreş, Korhan Karaoysal, Ali Kazma, Nar Photos, Desislava Şenay Martinova , Ali Taptik, Cengiz Tekin, Furkan Temir and Mehmet Ali Uysal. It will run from 2 July until 23 September 2018 at the Maison des Peintres during the Les Rencontres d’Arles festival.