An Interview by Selin Tamtekin with the artist regarding their current exhibition ‘all the birds would come to my garden’ at Depo Istanbul

Şafak Şule Kemancı, photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

I interviewed Şafak Şule Kemancı online a week before the opening of their first solo exhibition. all the birds would come to my garden has since opened at Depo Istanbul and will remain on view until the beginning of August 2021.* Organized with the collaboration of Sınır/sız,** this exhibition was timed to coincide with Istanbul’s vibrant LGBTQ + Pride Week.

When Kemancı appears on my screen, the artist sits at the desk in their living room in Istanbul. Behind, a sofa, some small, framed paintings hanging on the wall above, and a well-kept ivy positioned on a low stool, are all in my view.

Şafak Şule Kemancı, Untitled, 2020, polymer clay 16×17 cm, photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

“I grew up in London and was Shaped There”

“In the house, all the cupboards, everywhere are now bursting with artworks,” the artist states, for a moment bringing their fingers, adorned with dark nail polish, up to their forehead. Kemancı conveys the impression of being both excited and tired – but in a good way. Then they pick their phone up from the table and rise to show me some of the works intended for the exhibition.

After completing their high school education in Istanbul, Kemancı joined their father in London, where he still resides. Following obtaining a textile design degree at Central Saint Martins, they acquired a master’s degree in fine arts from Goldsmiths University. When I ask how the considerable time they have spent in London has influenced their artistic development, the artist responds:

“I moved to London aged 17 and lived there for 20 years. I can say I grew up in London and was shaped there.”

‘all the birds would come to my garden’, Depo Istanbul, installation shot, photo credit: Doğan Kemancı

Opulent Wallpapers Containing Queer-erotic Imagery

Kemancı’s art is filled with lavish textural diversity: exotic, fictional plants and liberated, naked bodies making love with climbing plants and snakes in polymer clay – a material typically used in arts and crafts; huge soft plant sculptures in latex, satin and velvet; wall hangings depicting glittery dildos; hypnotic flowers evoking vulvas painted on reversed glass and opulent wallpapers containing queer-erotic imagery.

The artist took up wallpaper design and printing at university. They created their first wallpaper as a part of their dissertation in their final year at Central Saint Martin’s College, where they specialised in printing.

“The Wallpaper Started as a Protest”

This wallpaper, adorned with images of women engaging in sexual acts with one another, carried the incentive of protesting against the prevailing social and legal discrimination towards gay people in England during that period. The artist reveals the story behind this first wallpaper, which they printed by means of serigraphy:

“I had made that wallpaper back in 2000. In those days in England, except for in their private homes, gays weren’t legally permitted to conduct sexual activity in any place which could be deemed public – this included hotels. If gay people walked on the street holding hands, they could be stopped by the police. These restrictions were only lifted in England through a new Act which came into force in 2003. In those days, I used to often hear this remark from supposedly open-minded people: ‘I don’t mind what gays do, as long as they do it between their own four walls.’ And I said, well in that case, I shall take my sex life, which must remain hidden, and make it public by transferring it onto walls. For this, I photographed my friends and lovers in erotic poses, printed these images onto wallpapers, then exhibited them. That’s how the wallpaper started – as a protest.”

Şafak Şule Kemancı, Untitled, 2021, polymer clay 17x20cm photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

“I Wished to Create a Living Space That is Happy Within Itself”

Yet, with time, this urge to protest, which influenced the artist’s earlier works, was replaced by a different tendency.

“As years passed and I reached a certain maturity, my works moved away from trying to explain my plight to cisgender people or rebelling against the system, and altogether shifted towards (wearing a bright smile, she opens her hands up in the air) celebrating our existence. This is a very soothing thing. For me it was a breath of fresh air that forged a new path.”

I touch upon how lately in Turkey, the violence and systematic discrimination LGBTQ + people experience hardly ever leaves the headlines. I point out that this exhibition, particularly in such times, bears considerable significance. Kemancı replies:

“I wished to create a living space that is happy within itself and isn’t bothered with explaining itself to anyone else.”

Şafak Şule Kemancı, Esra and Özge, 2020, digital print wallpaper, detail, photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

“We Need to Tell Our Stories”

In Esra and Özge a couple’s moments of lovemaking are part of a rich labyrinth ornated with baroque-like motifs of sinuous snakes, exotic plants and birds. This wallpaper covers a seven-metre-long wall which has been temporarily erected in the gallery space.

“Esra and Özge are my friends. I photographed them for this wallpaper. I’ve worked with other couples prior to this. When I work with couples, I don’t lead them in any way. I tell them they should do what they feel like doing and then I take multiple pictures. That’s what happened as well with Esra and Özge. I wanted it to be a romantic scenario that belongs to everyday life. That’s why, for instance, Özge still has her socks on. We need to tell our stories – this was my starting point for this work.”

Şafak Şule Kemancı, Untitled, 2021, mixed media, 180x90cm, photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

“I Don’t Wish to Make Any Reference to the Domestic Sphere”

Kemancı enters one of the rooms of their home, to which they moved nine months ago, and where they have produced the majority of the works for the exhibition. A few seconds later, a huge soft plant sculpture fills my computer screen. The peculiar plant has long tentacles that resemble tassels. The artist explains how, in the show, this untitled piece will be suspended from the ceiling with rope. Showing me the dark green satiny leaves of its base, they remark, “It has a cement base. In such pieces I always use cement, as if they’ve sprouted from the cement. I prefer to use cement instead of flowerpots, since I don’t wish to make any references to the domestic sphere.”

“A Lover You Carry Responsibility Towards”

Examining closely, one can detect that this plant has folds resembling male and female organs. Ecosexuality is one of the driving themes of this exhibition. Originally invented by sex worker and sex educator Annie Sprinkle and her partner Beth Stephens, this movement, which encapsulates desiring nature in a sexual way, incorporates a separate erotic dimension to the artist’s boldly inventive works.

When I admit to Kemancı that I’m coming across the term “ecosexuality” for the very first time, she responds:

“It’s a very beautiful concept. We always refer to nature as ‘mother nature’. It removes nature from its motherly role where you expect it to continuously give, and grants to it the role of a lover you carry responsibility towards.”

They then share an image of one of the works from the vulva series, which they have realized by painting in acrylics on reversed glass. It’s lying flat on a table, surrounded by bubble wrap, waiting to be wrapped up.

While the wallpapers were works the artist created during her time in England – taking their inspiration from England’s traditional interiors – reverse glass painting is a technique they have gravitated towards since returning to Turkey in 2012.

“It’s a procedure that pertains more to the East. I consider it an artisanship that’s common to Turkey. I prefer to work with materials that are used more in traditional crafts. My pieces could contain erotic or queer themes, or could be severe; I like this contrast between the materials and the subject matter. In the past, I painted on canvas, but that did not excite me as much.”

Şafak Şule Kemancı, Vulva series (No.2) 2021, acrylic on reversed glass, 50x70cm, photo credit: Nazlı Erdemirel

“A Playful Defiance Against Art’s Big-Headedness”

At the start of our conversation, the artist revealed how they consider artmaking an extension of the playmaking they once carried out as a child. They add:

“The material is also a part of the game. I like producing pieces from polymer clay, since it’s an arts and crafts material. At the same time, I regard working with such a material a playful defiance against art’s big-headedness. As for glass – I love its shininess”, she emphasises by narrowing her eyes.

‘all the birds would come to my garden’, Depo Istanbul, installation shot, photo credit: Tuğçe Ünlü

“Shimmering, Giant Snakes Under My Bed”

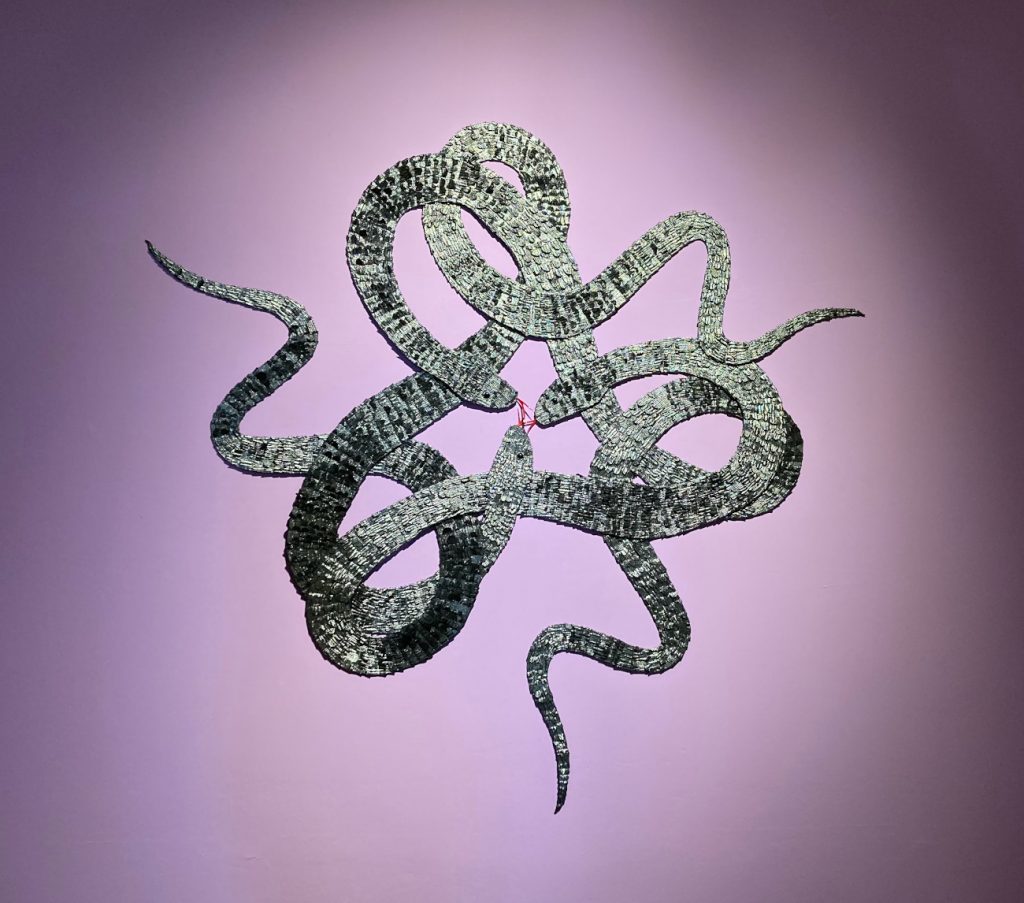

Lastly, Kemancı enters their bedroom. Kneeling down beside their bed, remarking “the shimmering, giant snakes are under my bed”, they open the large folder to show me the snakes. Having contemplated how their last sentence could potentially frighten most people, I smile.

Mounted on a violet wall, these snakes are currently greeting visitors at Depo Istanbul as they enter the ground floor gallery.

The snakes are entangled as if making love – they harbour themes the artist often renders in their work, such as eroticism that isn’t centred on humans, and polygamy.

In all the birds would come to my garden boundaries between species, plants and genders become fluid and increasingly blurred, and desires run wild – as if bursting from the earth like colourful flowers unexpectedly blooming in the desert, offering a timeless, alternative world to visitors right in the heart of Istanbul.

This article was first published in Turkish on the website T24

* Şafak Şule Kemancı, all the birds would come to my garden continues at Depo Istanbul until 01 August 2021.

**Sınır/sız is comprised of İlhan Sayın, Ozan Ünlükoç and Metin Akdemir who are independent activists/artists with LGBTQ + organizational experiences in Turkey. Sınır/sız organised group exhibitions with queer feminist artists, namely Sınırsız (2018) and Sınır/sız ALAN (2019).